You enter the cinema to lay witness to this thing called a film. You’ve read about the incredible inventions of Edison — first with Kinetograph, then the Kinetiscope — and how people look inside of it and actually watch moving pictures. Now the Lumiere brothers have something better — the Cinematographe! It’s a machine that projects the moving pictures onto a surface. Imagine that, moving pictures on a wall.

January 25, 1896. You’re filing in to view the latest Lumiere film, L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat). Your heart beats with anticipation, your palms clammy with excitement.

The lights dim and the Cinematographe pops on with a mechanical whir. The sound of the reels clambering along fills the room as an image appears on the screen in front of you.

People. They’re milling about on the platform at La Ciotat, clearly anticipating the arrival of a train at any moment. Even though the scene lacks color, you feel transported. In the distance, a black speck.

The speck is growing in size, seeming to rise from the horizon, getting bigger and bigger until — is it coming right at you? Your heart pounds and you recoil in fear. Others are running toward the back of the theater, climbing over chairs, screaming — trying to escape the iron maw of the train. Suddenly, it zooms right past like a spirit moving through you.

Although there are no longer any first-hand accounts of what happened that day, it’s believed that this story is an urban legend, what Martin Loiperdinger has referred to as “cinema’s founding myth.” Whether you choose to believe it or not, it’s an excellent illustration of the power of narrative, and how a good narrative can persist through time and tell us so much about the world.

According to the story, people were so entranced by the new technology that, despite all the evidence to the contrary — they were sitting in a cinema, there was no sound other than that of the projector, and the film was in stark black and white — the audience believed it was real. So real, in fact, that people recoiled in fear and ran for the exits so that they wouldn’t get hit by the train. So real, in fact, that even to this day, the myth persists with people landing on both sides of the argument.

This legend persists because it is compelling, and even in its simplest retelling, our hearts palpitate as our brains recreate the experience and fire off biological reactions. This, to me, is the power of a good story, something that neuroscience is beginning to understand. What we’ve learned through our studies of the last 30–40 years or so is that narrative is a fundamental construct for experiencing the world, one that separates humans from the rest of the animal kingdom. It’s the reason you should seek to tell great stories if you want to inform, entertain, convince, or otherwise educate people.

The need for story is woven in the fibers of our DNA. Since the first days of fire when man was huddled around the flames passing knowledge to the tribe of how to fend off a pterodactyl attack, we’ve relied on stories for the transmission of information. While it’s difficult to determine just when the first stories were told, we know that the oral tradition long predated any writing system. The capacity to use language likely developed in humans at least 100,000 years ago, and it’s likely that our penchant for narrative developed around this time as well.

Before paper, people carried knowledge in their heads in the form of stories. In fact, many ancient cultures had a chief storyteller in the tribe who was the fountain of knowledge and dispensed the tribe’s moral and cultural values by way of narrative. The oral transmission of information was a useful and easy method for sharing, but it was subject to the vagaries of the storyteller. It wasn’t until much later that man would recognize a need for a consistent form of knowledge capture and information transfer, inventing writing as a means of communication.

The Sumerians get the credit for first writing stories, most of which were scrawled on stone tablets in cuneiform, first originating around 3400 BC. The tablets contain mostly economic and administrative documents. Art emerged sometime later in the form of essays, poetry, hymns, and myths. The oldest known fictional story is the epic tale of Gilgamesh, which originated from the third millennium BC. Once we started writing, we never looked back.

It is our use of language that allowed us to deliver what was in our heads. What was in our heads were the narratives that allowed us to survive and create meaning. As meaning-making machines, we are constantly searching for the relationships between things. When we come upon a scene, we are reconstructing it in our minds, all the sights, sounds, smells — all the sensory information is accounted for and matched against an existing bank of information stored in our brains.

The human mind uses all this information and the relationships between memories as a vehicle for the production of meaning. For example, a car parked on the street may seem just a car until we approach it and look a bit closer. Then we get a sense of the car’s story. We can feel its warmth, so we know that it was recently parked there. We see the color of the car and we feel the weather around us. Is the car wet? But it’s not raining. Why could that be?

Our brains link up the bits of disparate information to form a cohesive narrative about the car parked on the side of the street. We may even tap into existing narratives, such as societal (Is it a luxury vehicle?) or personal narratives (Remember my first car) to add depth and complexity. From that meaning flows physical reactions to our world.

Our bodies are not comprised of a number of disparate systems acting in service of themselves. Rather, we are composed of systems that have a symbiotic relationship with one another, which is coordinated by mission control in the brain. Meaning invariably leads to emotions which produce physical reactions. This, too, is part of the brain’s job: to convert thoughts and feelings into physical reactions. And this is precisely what makes narrative so incredibly powerful.

Stories directly impact our audiences by engendering emotion. When you hear or read or watch a good story, it activates not just the language-center of your brain, but parts of the brain associated with touch, smell, movement, etc. Hearing the word banana not only produces a picture of a banana in your mind, but it also activates those parts of your brain that manage scent along with shape and color. And it’ll return emotions associated with a banana. You may be disgusted by the thought of a banana because it makes your tongue itch or there was that time when you comically slipped on a banana peel on your porch. What’s incredible is that the brain just doesn’t give a damn whether we’re actually seeing a banana, eating a banana, or hearing a story about a banana. The reactions are pretty much the same.

Now, consider the persistence of the Lumiere myth. In the story, people were so frightened by what was happening that they literally ran for the exits to get out of the way of an oncoming train that was in black and white, projected on a wall, couldn’t be smelt, touched, heard, or felt. This at first seems preposterous to us, but it only takes seconds for our brains to construct a narrative based on our own experiences about what it feels like to be in a dark place, to see a new technology that has never been fit for public consumption, and to be a part of the excitement and anticipation, the wonderful possibilities of our world on display. We can feel the tension.

When we read or hear the myth, the brain makes all the connections for us without any conscious effort on our part. It pulls together the sights, the sounds, the smells, and it packages them to produce meaning. This meaning triggers physical reactions in our body. We may find that our heart rate quickens or the palms sweat or the hairs on the back of our neck stand up. We’re nervous, anxious, excited, confused.

Why?

Because narrative is so fundamental to the human condition that it produces these effects whether or not we are participating. The only thing that varies is the actual intensity of what is happening, which can be heightened through the use of good storytelling techniques. What each of us carries then is the most powerful personal virtual reality machine in the universe.

So, how can we tell great stories, simply?

Because narrative is a fundamental building block of humanity, it means there is tremendous opportunity for its uses. A story well told can get ideas into people’s heads, motivate change, and even shift the worldview of a person. While it’s fundamental to the human condition, narrative is not a tool we think of using in our everyday lives.

The primary barrier to its use is that when we think of narrative, we see it as much too complicated to employ in most circumstances. We can’t see how it might form the structure of something like an essay, a Powerpoint presentation, or a live event. It’s like seeing one of your elementary teachers at the local grocery store — we think of it within the singular context of the arts, books, movies, poems, etc.

Instead, there’s a simple framework that can be adapted to fit within a variety of contexts. What does a story look like if I️ change the medium to say, a webpage? It looks differently, but ultimately it’s the same underneath. And the ability to deploy it in many different forms speaks to its versatility. So what’s the simplest structure we can employ?

Enter Stage Left: The Three-Act Story Structure

There are many different plotting devices for stories, but to me, one of the simplest ways to think of this is like the screenwriter — the three-act story structure. The majority of stories, especially convincing ones, are based on this simple framework. While the three-act structure was originally conceived to describe plot in terms of screenwriting, I find it’s a helpful construct for describing what is actually a simple, fundamental structure.

Here’s how it works.

Act I

Act I is all about exposition, or context setting for what’s happening, and ends with an event that changes the main character’s life. That event proposes a question that the remainder of the narrative attempts to answer. Don’t overcomplicate things here. The main character could be you, the storyteller, or it could be a friend, a colleague, or a business partner. It could even be a business. The point is that something is changing and what follows will be an attempt to resolve the conflict that is created by that change. Remember, for as flexible of creatures that we we think we are, change is challenging and sometimes difficult.

Act II

Act II depicts the attempts to solve the problem. At any rate, in Act II, the goal is to increase the tension until we reach the dramatic peak, the climax. Our main character tries different ways to solve the problem and each yields different results. The tension increases as it boils to the climax, which is the peak of the narrative tension.

Act III

Act III is the resolution of the conflict introduced by the change in Act I. It’s where we wrap things up and show what’s changed and how things are different from where we started. At this point, the narrative journey is complete, and we may talk about things like next steps.

Deploying the Three-Act Structure

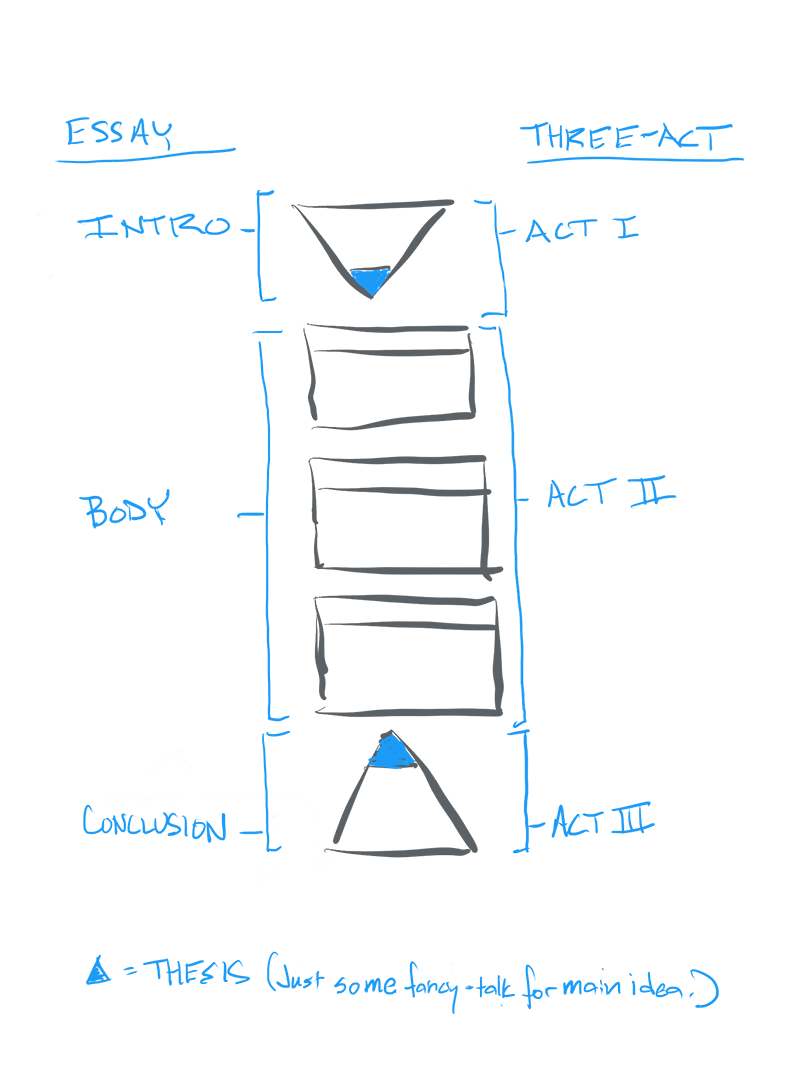

In an essay, we can think of the structural elements as: intro, thesis, body, and conclusion. The goals of each map to the three-act structure:

- Act I: The introduction — The introduction provides the context for the rest of the piece and ends with the thesis. It generally answers the following questions: What problem are we trying solve? What’s in it for me (as a reader)? Why should I care?

- Thesis statement is fancy-talk describing a succinct statement of your position on the topic that you just introduced. It sets the audience up for what comes next. If you think about it within the context of the three-act structure, it is the change for the protagonist, or the question that the rest of the narrative is trying to answer.

- Act II: The Body — The body is where you make your arguments for whatever you’re ultimately trying to prove. In your essay, you will spend each block describing the arguments in favor of your thesis, as well as debunking the common arguments against your thesis. The work through this section should build to the climax, or the point at which the conclusion is obvious to the reader.

- Act III: The Conclusion — The conclusion is where you come back to your thesis to show that your arguments have built a case for what you proposed. You show how you answered the challenge proposed by the thesis, how things are different, and again, what’s in it for the reader. The reader should have no doubt where you stand on a particular issue. Image for post

Essay structure = three-act structure.

As you can see, the three-act structure can easily be extended to undergird an essay. The only thing that’s changed is the delivery vehicle, but the overall structure remains intact. As we do in essays, we can similarly structure, say, a PowerPoint presentation. The same argument could easily be made in a PowerPoint presentation.

An easy way to visualize this is to create an outline. In the outline, you can list your context, your thesis, and each supporting detail, as well as all the details for Act III. Then you can think about what visuals could accompany the right words to capture the essence of your argument. Remember, a presentation should support the argument that you’re making, but the real delivery is oratorical. Use simple words and phrases to support and reinforce your key arguments. Do not fill slides with words. You want to pull people through the story, and your visuals simply help drive home your main points. Ultimately, people have come to hear you talk.

Once you begin to structuring your work in the form of narratives, you’ll creates resonance for your audience. Resonance is that feeling that people get when something connects deeply with them. The more they can relate to what’s being said, the stronger the connection you can make with them, and the more receptive they become.

So the next time you have to put together a PowerPoint presentation or make a pitch or try to sway an audience, take some time to think of your approach within the context of a narrative. You’ll find that it’s a very easy way to communicate with people and that they are receptive to what you have to say, because ultimately, it’s the fundamental form of human communication.